By Kevin Barrett, for Al-Andalus Tribune

Agadir is a major city on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, south of Marrakesh and Asfi. As the urban hub of southwestern coastal Morocco, it’s all the way across the country from where I live in Saidia, the far northeastern corner where the Algerian border meets the Mediterranean.

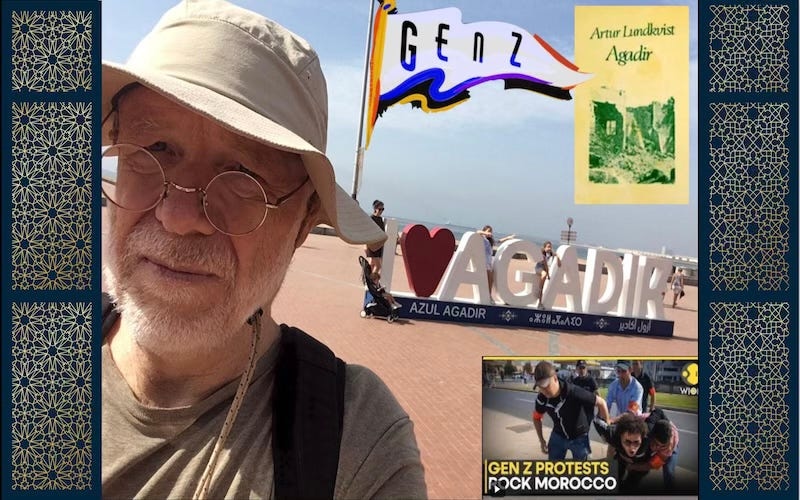

I decided to visit Agadir for various reasons, or maybe no reason at all. First, Ryan Air dangled the prospect of a $30 roundtrip flight. Then I remembered the book Agadir by the Swedish poet Artur Lundqvist—an unforgettable description of the devastating 1960 earthquake that leveled the city. I thought of Gaza, which now looks a lot like Agadir after the quake.*

If Agadir could be rebuilt into a thriving seaside community, so can Gaza. I resolved to visit Agadir to take in the results of all that rebuilding. Tomorrow Gaza, Insha’allah.

Contemplating a trip to Agadir, I tried to recollect what I once knew of the Sufi saints and religious revivalists who emerged from Morocco’s Sous region to leave their mark on North Africa, Al-Andalus, and the world. Among the Sufis, Sidi Ben Slimane (al-Jazuli), one of the legendary seven saints of Marrakesh, is world famous for his Dala’il al-Khayrat (The Guides to Goodness), a collection of prayers and blessings upon the Prophet ﷺ. And of the politically-active revivalists, the two biggest were the Murabitun (Almoravids) and Muwahhidun (Almohads), both of which exploded out of southwestern Morocco to unite North Africa and Islamic Spain (al-Andalus) from the 11th through 13th centuries c.e., corresponding to the 5th through 7thIslamic centuries.

And I thought of a more recent wave of activism that has emerged from Agadir: the Generation Z movement. The protests that rocked Morocco last month began September 1 at Hassan II Regional Hospital, where several women died in childbirth allegedly due to unsafe and unsanitary conditions. They grew throughout September and went nationwide.. The demonstrators, most of whom are teenagers, are asking why billions of dirhams are being spent on soccer stadiums and related infrastructure for the 2030 World Cup, while many parts of the country struggle with sub-standard health and education facilities.

I believe the protesters when they say that Morocco’s public hospitals need an upgrade. I know that from firsthand experience, having seen the inside of one in 2017. Temporarily paralyzed after a body surfing accident, I was taken to a public hospital in El Jadida, a few hours up the coast from Agadir. (I told the long version of that story in the article “The Moroccans Who Saved My Life.”) The doctors and staff at the hospital were kind and professional. They quickly took X-rays and determined that my spine wasn’t broken. I was suffering from spinal shock syndrome, with a good prognosis for recovery, meaning I wouldn’t be paralyzed for life. They prescribed pain medication, half-carried me to my friends’ car, and gently loaded me into the back seat.

I was so happy with the good care and good news that I would have given the hospital a five star review, except for one thing: When I asked to use the bathroom, the medical staff strongly recommended against it. They told me I definitely didn’t want to even see that toilet, much less use it.

The paradox of excellent doctors and nurses offering competent care equipped with serviceable X-ray equipment yielding quick, accurate results, at no charge whatsoever—a situation that compares favorably to American hospitals—condemned to work in a facility where the bathrooms can’t even be seen, much less used, seems emblematic of where Morocco finds itself today. The people are wonderful, and many are highly skilled. The infrastructure is uneven but improving. Yet huge lapses remain. And the young people, Generation Z, are impatiently demanding a major renovation.

As I wandered around central Agadir, my first impression was that it didn’t look underdeveloped or decrepit. Rather, I saw a city of wide, tree-lined boulevards interspersed with plazas and cafes, apartments and office buildings, freshly-painted white and gleaming in the south-Moroccan sun. The streets and sidewalks are teeming with people, not just locals, but also tourists from other parts of Morocco as well as foreigners. It actually feels strange to me to see so many gawris a.k.a. rumis (white people) in this beachside town, since they are so rare in my own beach town of Saidia. I have also noticed quite a few English-speaking sub-Saharan Africans, another category I rarely see in eastern Morocco.

This cosmopolitan, modern character reflects the way Agadir is in some ways both the most Moroccan—and in others the least Moroccan—of Moroccan cities. It’s the most Moroccan because it was totally rebuilt in the early years of independent Morocco, so the city as it stands today is not the product of the French-Spanish colonial period in the way that other Moroccan cities are.

But the fact that Agadir is 100% Moroccan-built ironically means that it doesn’t have a traditional Moroccan old city (medina). The cities colonized by the French and Spanish all feature a bifurcated design with central Moroccan medina or old city (al-medina al-qdima) and a European-style new city (al-medina al-jdida). The French, in particular, took great pains to preserve the traditional medinas with their ancient styles and crafts. Here in Agadir, the old city, and much of the new one, were totally demolished by the 1960 earthquake. Rather than rebuilding what had been there, the authorities decided to instead lay out a European-style city lacking an authentic medina al-qdima. Then in the 1990s the city fathers built La Medina d’Agadir, designed by Italian architect Coco Polizzi, a sort of fantasy reconstruction of a traditional medina. But it isn’t in the city center, and it seems more of a Disney-esque re-enactment than an authentic Moroccan medina.

Today’s rebuilt Agadir sprawls mostly to the south of where the pre-earthquake city stood clustered around the hilltop Kasbah (Agadir Oufellah). That area was never rebuilt and remains a green space. You can get to the Kasba via Morocco’s first cable car, starting near the marina.

So what do the locals think about the way their country is developing, and in particular the Gen-Z protests? Kamal, a café owner, expressed the consensus view: The demonstrators have a point. There’s a disconnect between the unevenly booming economy and the even more uneven infrastructure, especially in health and education. Though most Gen-Z activists are good people, Kamal said, the protests were infiltrated by Polisario activists paid by the government of Algeria.** A mix of these provocateurs alongside clusters of angry unemployed young men were responsible for the violence that broke out on October 1. And of that there was plenty, in several cities, including Agadir. The troublemakers, whoever they were, rioted, attacking police, burning cars, and smashing windows. Three people wound up dead, 28 injured, and as of this writing almost 1500 have been arrested and over 2400 charged.

According to Kamal, the activists’ decision to demand money for social services rather than soccer stadiums was a double-edged sword. Though it sounds reasonable—why spend colossal sums on sporting events when your services are so uneven—soccer is extremely popular here, and the vast majority supports hosting the 2030 World Cup. Kamal said that the same young people who support the Gen-Z protests are also wildly celebrating Morocco’s October 9th U20 World Cup victory. So it isn’t like they want to cancel hosting the World Cup, stop building stadiums and transit infrastructure, and use the money for schools and hospitals. Well, maybe a few do. But most are not really opposed to the government’s soccer-vs.-health-and-education priorities. Since there is no specific demand that the majority can agree on—“end corruption” is not very specific—the movement will probably either fizzle out, or morph into something other than “services vs. soccer.”

Kamal waxed enthusiastic about the economic growth he has witnessed since he opened his first café in the 1990s. Admitting that the tourist trade has its downsides, including the alcohol, gambling, and prostitution that follow tourism everywhere it goes, he nonetheless thinks Morocco is heading in the right direction, citing strong long-term economic growth, improving education, and championships in sports ranging from soccer to surfing. He also appreciates the resurgence of Amazigh (Berber) language and culture, which has emerged from rural villages onto road signs and radio stations during the past few decades. (Like many in this region, Kamal is a native speaker of Shilha, a dialect of Amazigh.)

Kamal asked me whether I was planning to learn Amazigh. I told him that as a 66-year-old speaker of good French, passable Arabic, and substandard Spanish, I’m not sure my brain has room for new languages, especially ones with odd-looking alphabets.

The increasing prominence of Amazigh, as far as I’m concerned, is just making Morocco even more colorful and confusing. (Some might say Morocco needs to be more colorful and confusing in the same way the Eskimos need more snow, but that’s another topic for another time.) So I told Kamal that I have no immediate plans to learn Amazigh…but there is always an insha’allah.

–

*Zionism-quakes are much worse than earthquakes, since earthquakes don’t shoot down starving homeless victims lining up for food, and since earthquakes are said to be acts of God, while Zionism-quakes are done by devils.

**Morocco and Algeria have long been at odds over a territorial dispute focusing on the resource-rich Moroccan Sahara, which Algeria seeks to dominate through its proxy separatists, the Polisario. Though I agree with much of Algeria’s pro-Global-South foreign policy, I think Morocco is right about the Sahara. Kamal’s claim that Algerian provocateurs were behind the Gen-Z violence is widely credited in Morocco. It’s also not implausible, given that color-revolution style movements dominated by young people mobilized through social media are often used by governments in attempts to destabilize other governments.

Some images from the Agadir Museum of Art suggestive of the mysticism that Morocco in general, and the Sous region in particular, are known for: